Hélène Gaudreault is full of emotion when she talks about her daughter Karine’s early life. Karine is now 24 years old and has a full-time job, but for most of her childhood and adolescence, she suffered from several medical conditions and needed daily insulin injections for diabetes. It was a discovery at the MCH that changed everything for the better.

Within a few days of Karine’s birth in 1988, Hélène knew something was wrong. Karine wasn’t eating or drinking, so Hélène decided to return to Charles Lemoyne Hospital where she had just given birth. Within a week, Karine was transferred to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at the Montreal Children’s Hospital. She was investigated for many different conditions, and was eventually diagnosed with diabetes.

Karine had to be transferred to another floor for monitoring, and it was three months before the family could go home. By the time they did, Hélène had learned how to regularly test Karine’s blood sugar and give her twice-daily injections of insulin.

In the years that followed, Karine was also diagnosed with other conditions. At age two, she was put on depakene for epileptic seizures, and at age six, she was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder.

A discovery that changes everything

When Karine reached the age of 16, she started to see Dr. Laurent Legault for her diabetes. Dr. Constantin Polychronakos was also involved in her care.

Not long after that, Hélène got a call out of the blue from Dr. Polychronakos. He told Hélène that researcher Rosemarie Grabs had identified a gene mutation in Karine, one that made her a perfect candidate to try an oral antidiabetic treatment instead of daily insulin injections.

Hélène talked to Dr. Legault, then decided to try it. They planned a two-week transition, during which Karine would be weaned off insulin injections and start taking glyburide pills three times a day.

Dr. Legault explains that Karine was the ideal candidate to try the treatment. “This medication is commonly used in patients with type 2 diabetes,” says Dr. Legault. “In certain rare patients, insulin production is dormant. Glyburide opens up the pathway which helps to restore this production and allows people to achieve normal blood sugar levels.”

Drs. Legault and Polychronakos called Hélène every day to check Karine’s blood sugar tests until she completed the transition. Hélène says it was much easier than she had anticipated and in the end, Karine’s dose was stabilized at two pills, two times a day.

Beyond expectations

To be free of the responsibility that comes with daily injections was a tremendous relief for Hélène. But what else happened was far greater than anything she ever expected. Up until the age of 16, Karine was not a very social or expressive child. “You could say that the new treatment was a sort of liberation for Karine. Her behaviour and demeanour completely changed for the better.”

Karine now works five days a week at L’école Aérotechnique de St-Hubert on a project sponsored by the Centre de réadaptation en déficience intellectuelle (CRDI). She has also developed her hobbies and interests: Hélène says she’s a whiz at jigsaw puzzles, and knows virtually every song on the radio—artist, title and lyrics.

Once a month, Karine participates in a weekend retreat with a program called Aux Quatres Poches, where she gets to socialize with other young adults with handicaps. Hélène, who is on the board of directors for the program, says it has given her family the opportunity to get a bit of respite and has also allowed Karine to feel independent and to socialize with others.

According to her mother, Karine has evolved significantly. And she is still evolving, which is exciting for the family. “My life was pretty difficult before Karine started her new treatment. I was the one who had to inject her with insulin every day for 17 years. It was very stressful at times. But once she started her new treatment, I had more time to spend with my other daughter, Stéphanie, and with my partner. Honestly, it changed all our lives for the better.”

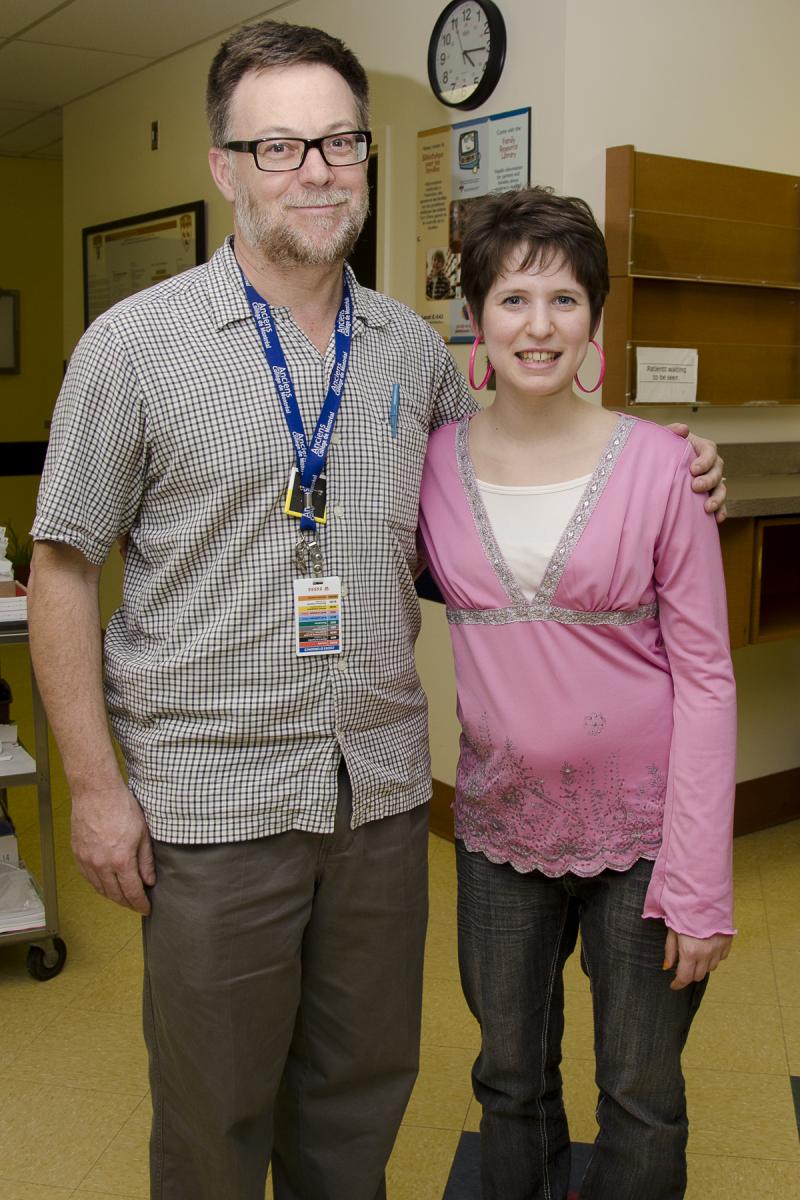

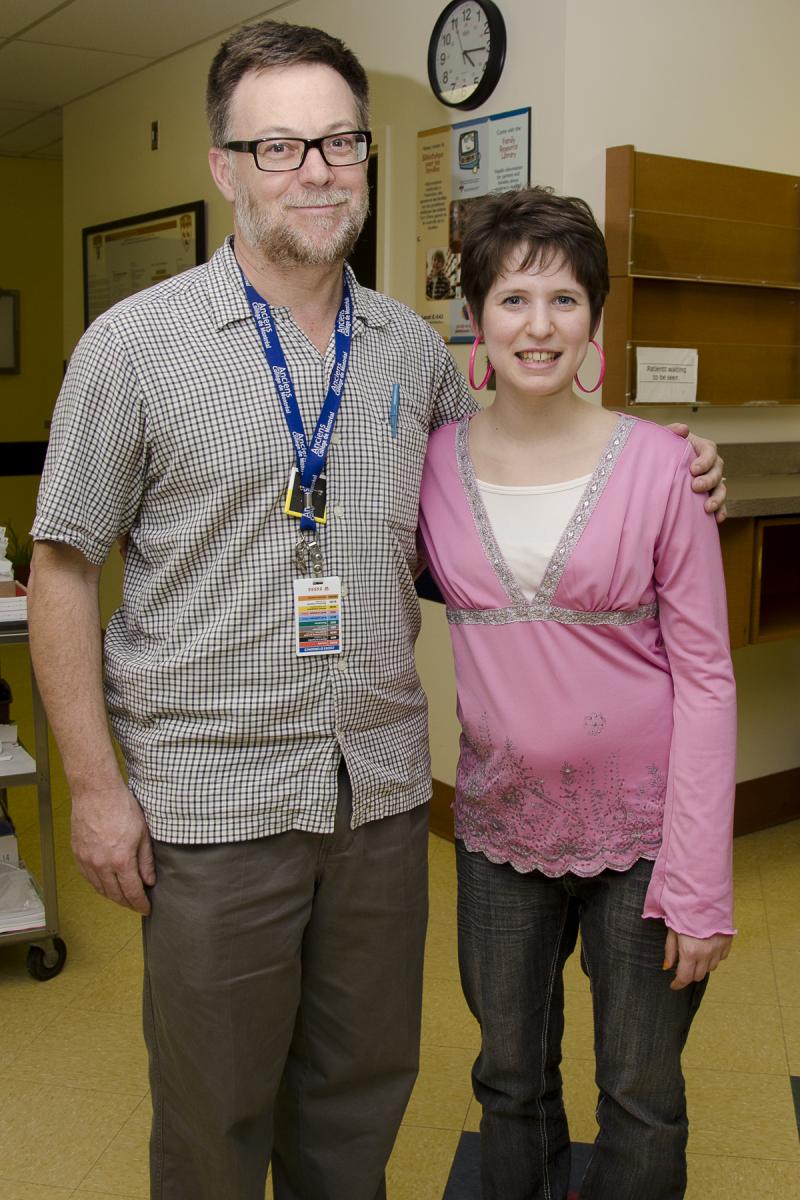

Note: Karine is taking part in an exhibition of 30 photographs entitled

Porter un regard différent sur la déficience intellectuelle, which asks us to see intellectually challenged people in a new light. Its organizers hope to offer a different point of view, a fresh perspective on their sensitivity, intelligence, creativity, passions, strengths, pleasures, friendships and love. The subjects depicted in the photographs are continually encouraged with support from their families, friends, and communities. They are generous and participate actively in society. Valued by those who know them, they also provide us with wonderful life lessons. They are not just men, women, and children to whom something is owed—they are active agents in their own lives, in a position to give back. And it is no coincidence that the term intellectually challenged reflects the daily challenges they face, obstacles they have to meet and surmount, and they do so with grace. The 30 photographs and the stories behind each portrait have been compiled in a soon-to-be-published book. You can follow the project at

www.chutregardez.com.

When Karine reached the age of 16, she started to see Dr. Laurent Legault for her diabetes. Dr. Constantin Polychronakos was also involved in her care.

When Karine reached the age of 16, she started to see Dr. Laurent Legault for her diabetes. Dr. Constantin Polychronakos was also involved in her care.