Novel gene therapy offers rare hope

29 February 2020

Eighteen-year old is first Canadian patient and ninth globally to participate in a second-phase clinical trial to better understand Glycogen storage disease type I

At just 18 years old, Samuel Gauthier is already a pioneer for patients eager for better treatment options for managing his extremely rare disease. Samuel is the first Canadian and the ninth patient worldwide to participate in the second phase of a study using gene therapy to treat Glycogen storage disease type I, otherwise known as GSD.

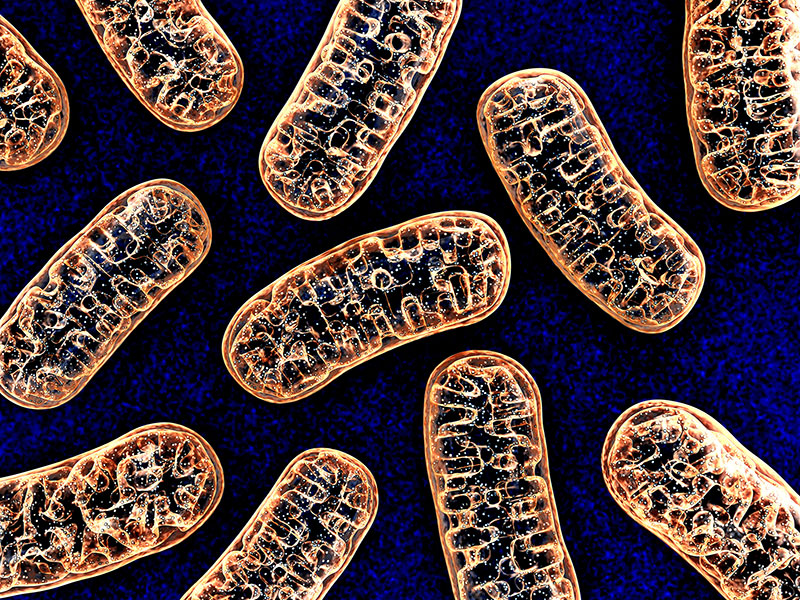

Samuel is one of roughly 6,000 patients worldwide and 20 in Quebec who are known to be living with this rare genetic metabolic disorder, characterized by an inability to break down glycogen (a stored form of sugar in the body) to create glucose. “Basically, my body isn’t able to produce glucose or store it like others can,” he explains. This creates a constant risk of hypoglycemia (or low blood sugar levels), leading him to feel dizzy, weak and hungry if he doesn’t eat every 2 to 3 hours. It also places him at risk for seizures and even death if his brain were to lack access to glucose during long periods of fasting.

“When we are fasting, we need useable fuel. Once we have used the glucose in our blood, , our bodies can use glycogen, which is excess glucose that has been stored away (in the bank) for future use,” explains Dr. John Mitchell, director of the Montreal Children’s Hospital’s (MCH) Endocrinology division and an expert in rare metabolic diseases at the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC). “In Samuel’s case, his body can’t leave the bank with glucose. His body will start to break down the glycogen but will instead create toxic by-products or chemicals. In addition to low blood sugar, this can result in increased lipids, high triglycerides, high lactate, and increased uric acid in his body. These elevated chemicals can cause gout and cause long term damage to his liver and kidneys.”

Until now, the only treatment option available for patients like Samuel has been twofold: a constant monitoring of glucose levels to ensure his blood sugar is in an optimal range, coupled with timed consumption of “shakes” containing specific ingredients to help maximize blood sugar control, nutrition, and energy.

“Samuel relies on feeding frequently and this has been the case since infancy,” explains Dr. Mitchell. “His ‘shakes’ are made up of 30 to 40 grams of raw, uncooked cornstarch mixed with a soy milk formula, which he takes every 2 to 3 hours – even waking up overnight to drink them. Because cornstarch is a complex carbohydrate, it provides a steady amount of glucose that is more slowly digested than other options. Given throughout the day or night, it can help keep blood sugar levels within a normal range.”

But having to maintain a rigid feeding schedule for a lifetime has significant effects on the quality of a patient and family’s lives. “As you can imagine, the idea of going low during the night is extremely distressing to families,” explains Dr. Mitchell. “It’s not infrequent for family members and for patients to express a lot of worry in managing and controlling the disease. When you add sleep deprivation on top of it, it’s life-altering.

It’s a sentiment echoed by Samuel, who has had to adhere to a very rigid feeding and sleep schedule to help manage his illness. “I have to put alarms on at night to wake myself up and drink my shakes. I can’t eat just anything I want. I have to constantly be aware of my glucose levels and I have to bring a backpack with me filled with my supplies whenever I go out. It would be amazing to not have to wake up every few hours and not have to focus on always going low.”

Gene therapy trial offers glimmer of hope

When Samuel turned 18, he graduated from pediatric care and became very intrigued by a new clinical trial being offered by Medical Genetics at the MUHC – the only centre for this trial in Canada – that had the potential to find novel ways to manage a disease that while rare, greatly affected his family’s life and the lives of thousands of others.

“As soon as Dr. Mitchell mentioned this as an option, I was interested and wanted to participate,” says Samuel. “This was my chance, and I had to take it.”

Dr. Mitchell shared the details of the study with Samuel, explaining that this would be the first round of testing on humans. “The trial is small with only 9 to 12 patients worldwide,” he explains. “The goal is to study whether injecting the body with a over a trillion viral particles that contain the DNA for the gene Samuel is missing can actually help his body break down glycogen. This particular phase of the trial is examining the safety and efficacy of the dose of viral particles. But a secondary goal remains: does this work?”

On December 4th, 2019, Samuel received a one-time infusion that would deliver a new copy of his missing gene to his liver via a naturally occurring virus. In order to test whether or not the therapy has worked, Samuel agreed to undergo regular blood testing, medical imaging and physical exams as well as EKGs over two to three months. It’s this rigorous research protocol that will provide Dr. Mitchell and the team behind the study valuable data to evaluate whether the dose was effective and how his body has responded.

“Throughout the trial, we’ll try to decrease the amount of cornstarch he’s taking and actually wait for him to go low (have a hypoglycemia) to see how long he’s able to fast on a fixed dose of cornstarch,” says Dr. Mitchell. “If the injection works as we hope, the thinking is that we can increase the amount of time Samuel is able to fast to 6, 8 or maybe even 12 hours – which would equal much more restorative sleep and a greater flexibility in managing his disease. We don’t know if it will work and how long the effect could last – whether it will be a year or his entire life. But if it does work, it could dramatically improve his quality of life.”

“Things are going well and I feel lucky to have had this chance,” says Samuel, who continues to participate in Facebook groups dedicated to patients who have become experts in managing a little-known condition. “I look forward to finding out the results of the study to see if the treatment worked.”

“It’s important to be involved in these studies because it gives our patients hope and an opportunity to participate in something that may be beneficial,” says Dr. Mitchell. “We’re getting closer to understanding this disease more, and I think that’s an exciting thing.”